Britain and Hawaii have a complicated history marked by surprisingly cordial relations in the face of considerable adversity.

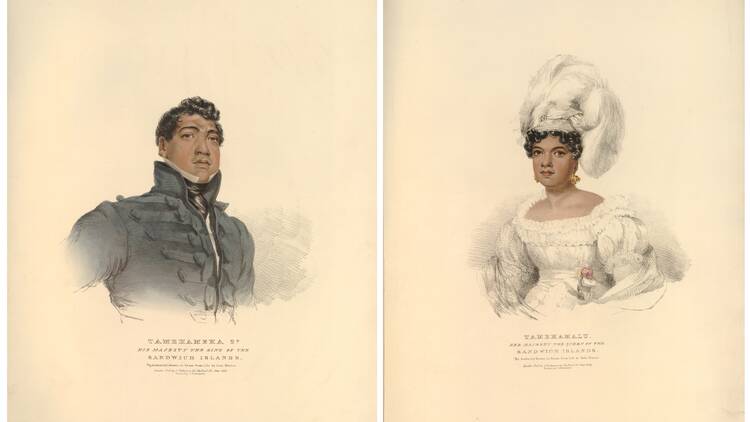

Captain Cook famously met his end in a skirmish on Hawaiʻi Island in 1779. Then, almost 50 years later in 1824, King Kamehameha II and Queen Kamāmalu – monarchs of the now united archipelago – came to London on a diplomatic mission to shore up support from the Empire. Tragically, they both died of measles while waiting for an audience with George IV. But the visit went well diplomatically. After a rogue British captain seized control of the islands for five months in 1843, the Royal Navy booted him out and restored sovereignty (though Queen Victoria sort of shrugged helplessly when asked for help following Hawaii’s annexation by the Americans in 1893).

This is all by way of say that Britain had as close a relationship with the Kingdom of Hawaii as anyone during its 98-year existence, and this led to a relatively large amount of cool Hawaiian stuff being acquired by the British Museum and Royal Collection over the years: some of it, inevitably, under shady circumstances, but for the most part accumulated by trade or as lavish royal gifts. And it also means there’s a good story: new exhibition Hawaiʻi: a Kingdom Crossing Oceans does offer some background on the archipelago’s pre-monarchical past and American future, but it largely focuses on relations between our two kingdoms and the ill-fated royal visit.

There’s plenty of fascinating stuff here, from gorgeously sinister puppets to some enjoyably lurid weaponry

Much of this expertly curated exhibition revolves around a series of astonishingly vibrant colourful costumes and cloths that seem to have weathered the last two centuries astoundingly well: reds, yellows and blues about in an exhibition where many of the items are made from the feathers of birds that no longer exist, their colours shining on years after their extinction. The most lavish of all is a gargantuan feathered chieftain’s cloak made as a gift for George III (whose death in the interim meant it defaulted to his son).

Traditionally a chieftain’s cloak wasn’t allowed to touch the floor: special dispensation was obtained for the megacloak – not seen in this country since 1900 – which would need to be worn by somebody north of seven foot to avoid touching the ground. It’s wittily paired with George IV’s bejewelled coronation outfit – the point that all monarchy wear ostentatious ritual clothes is maybe obvious, but the emphasis on kinship between the kingdoms is agreeable.

The cloaks are the showstoppers, and in some ways the story Hawaiʻi: a Kingdom Crossing Oceans tells transcends the specific objects on display (always a good sign). But there’s plenty of fascinating stuff here besides, from gorgeously sinister puppets to the otherworldly kiʻi – idols of deities – and some enjoyably lurid weaponry, including what I can only describe as a shark’s tooth knuckleduster.

The occasionally tense but strangely cordial relationship between Britain and Hawaii has largely been lost to memory: inevitably, American annexation has radically altered our perception of the former sovereign kingdom. But Hawaiʻi: a Kingdom Crossing Oceans is a startling vibrant and lucid window back into this vanished past. Hawaiian culture and customs have by no means disappeared, but this exhibition evokes its zenith wonderfully.